Growing pains

Have the boundaries for what makes a coming of age film shifted as the stretch into adulthood becomes murkier and less defined?

I have been wondering lately when I plan on growing up. Is it something that will happen magically overnight, will I wake up one day and think ‘well look at that, my life has really come together’? Or will the pieces of my life fall into place magically over time, and when I look back in a year or two I’ll see all the changes I instinctively made to live a more adult existence? You see, I’ve always loved coming of age stories, but even as I have slowly grown out of the ages of the teens I could relate to in these films, I’ve never grown out of the moods and concerns that are tied to them - the distinctly adolescent, not grown up moods and concerns. So at what age exactly, does one become ‘of age’? When do we grow up? And have the boundaries for what makes a coming of age film shifted as the stretch into adulthood becomes murkier and less defined?

I recently watched Joachim Trier’s The Worst Person In The World – and whilst the protagonist celebrates her thirtieth birthday during the film’s run-time, so much of what the film represented to me was tied in the same coming of age themes I’d seen in films explicitly dealing with teens: Mainly, a sense of snatching any identity that comes their way, in desperate attempts to define themselves as something real and definite - something adult. For Julie, those identities are wide-reaching and often changing – she wants to be a doctor, or a psychologist, or a photographer, or a writer. This theme of trying on different versions of yourself is a common trope in coming of age films, but usually, by the end of the film the (teen) protagonist finds the ‘right’ version of themselves, and they go off into the world armed with the knowledge that they’ve found the version of themselves they’re meant to be, as they venture into adulthood (although that’s certainly up for debate in regards to the now-infamous makeover scene in The Breakfast Club). That feeling, however, is shown just as powerfully in The Worst Person in The World as it is in The Breakfast Club – this core tenet that makes up what a coming of age story is, the panic over who we’re supposed to be and how we’re supposed to present ourselves, is something that isn’t really tied to teen years at all - and it certainly doesn’t disappear as we age.

Diablo Cody is obsessed with the teen experience - she admits this herself, stating ‘I cannot relate to adults very well. A lot of so-called mature movies don't speak to me. They bore me. I don't care about married people's problems. I am more interested in who is going to the prom with who.’ Her films, of course, speak about a lot more than this – she’s particularly adept at showing us how teens make the same messy, complicated choices that adults do. Even Diablo Cody’s Young Adult, which focuses on a woman in her late thirties, highlights how little difference there is between the teen version of the protagonist and the woman she became - the protagonist returns to the small town where she spent her teen years, with the film mostly serving to show us that she hasn’t really ever grown up from the girl she was in high school – but do we ever?

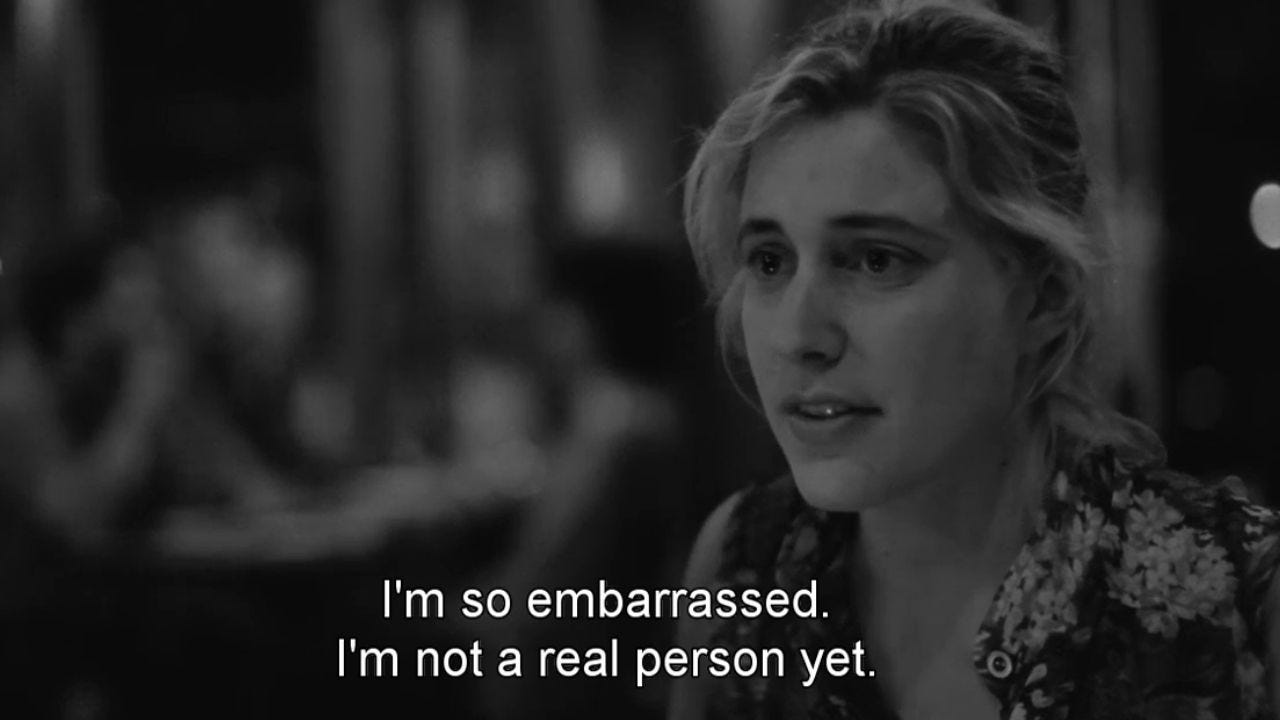

I guess what I’m saying is that most of the defining themes of classic coming of age teen movies can also be found in films where the characters are at far later stages of their lives. Take Frances Ha for example – A twenty-seven-year-old woman who floats from apartment to apartment, job to job, watching friends get engaged, get great careers, live generally ‘adult’ lives whilst she dreams of being a dancer and play-fights in the street. If the definition of coming of age is defined by a moral growth and a transition from youth to adulthood, this can surely be found in Frances Ha’s ending – she takes a less exciting, but more stable job, and reacts maturely towards her best friend who earlier she raged at for abandoning her. All this, and she’s far closer to her thirties than she is to her teens. So what’s the cut off point for this so-called transition into adulthood? I’d wager it can happen at any time in life, and that coming of ‘age’ isn’t really about age at all. After all, as Jenny Slate’s character Emma proclaims in I Want You Back: ‘Twenty nine is the new sixteen!’