Lollywood, Piracy, and Pakistani Film

A love letter to Lollywood from City Road, Cardiff in a belated NCA July 2022 newsletter

A series of video cassette tapes with different colours and alphabets adorn the shelf under the glass counter. Enveloped by a warm yellow light from the overhead fluorescent tubes, a myriad of people walk in and out, looking for everything from sandalwood soap to dried mango powder. South Asian grocery shops in the 1990s provided food, spices, herbs, halal meat: and, sometimes, even pirated films. A mixture of contemporary and newer titles was usually offered, along with classic films from the Pakistani and Indian film industry.

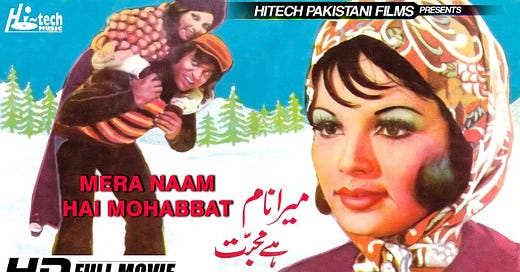

From the late 1940s onwards, the city of Lahore in Panjab was the centre of Pakistani cinema, known as "Lollywood". A portmanteau of the words "Lahore" and "Bollywood", Lollywood was both an immensely prolific and popular industry that reached its height in the golden era of the 60s and 70s. The deposition of Bhutto in a military coup nearly half a century ago by Ziaul Haq in 1977 saw the country undergo a process of Islamification under his dictatorship, with a strict impact on culture and film. The numerous films that poured out from Panjab would dwindle, and Haq imposed strict regulations on the production and creation of films. Cinema became contraband. The pirated copies of films like Mera Naam Hai Mohabbat and Armaan stood as an archival record of a Pakistan before the Haq regime that existed only within the living memories of the elders, a glimpse into a Pakistan from the youth of our grandparents.

As technology progressed, loaning videos or recording one of the many late-night Bollywood films on Channel 4 didn’t quite cut the mustard anymore. VHS combination sets or VHS cassette players were no longer a status symbol, households soon upgraded to DVD players, and the more affluent families purchased computers. An internet connection, a DVD-RW on a computer and access to pirated films bore a renewed fervour for the piracy of South Asian films and music amongst our own community- there was a boom of piracy across wider society, too. By this point, it’d gone from VHS tapes to DVDs to torrent sharing on peer-to-peer sharing sites. For a certain time period of time in the late 90s to the 2010s, it wasn’t unusual for someone to be selling pirated films in the pub, or to see pirated copies of Hollywood films at a friend’s house.

Thea Berry wrote in her piece for No Content Available that after the launch of YouTube in 2006 she would regularly use the website as a resource to source film material. She points out that "so much in the history of cinema is still inaccessible. Either it's in archives, or if DVDs have been reissued then they're at an inaccessible price point for a lot of people, or simply it's lost and out of circulation, or it's not on any streaming sites.”

The above is pertinent to my own experiences, too: Slackistan (2010) was released in 2010 and despite being released to critical acclaim, it was banned in Pakistan. Slackistan was widely pirated after it was banned, in Pakistan and worldwide amongst the Pakistani diaspora. Banning films only makes audiences want to access them more.

As Thea pointed out, a huge amount of cinema is still inaccessible, or extremely hard to access, including South Asian cinema. Slackistan, unsurprisingly, isn’t available to stream online. I’m not sure it was released on DVD, but it was heavily influential for a generation of Pakistanis. A DVD of the seminal Partition film Train to Pakistan will set you back nearly £20, but it’s available for free online. YouTube has become a digital archive and repository for 20th century Lollywood and Indian film, with the Lollywood classic Warrant (1976) starring Noor Jehan the “Queen of Melody” having amassed half a million views on YouTube over the past five years alone. Other films featuring Begum are unavailable on most mainstream streaming websites, but they’re online for free. Many of these films are available in the School of Oriental and African Studies university library in Russell Square in Bloomsbury, central London and other institutions: a world away from Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic Wales.

Shops that sold DVDs like Fopp, and Virgin Megastore have disappeared from our high streets. Nowadays, many laptops aren’t made with a CD drive, even if you manage to find a hard copy of a film. The digitisation of older Pakistani and Indian films combined with sites like YouTube enables us to bridge the gap in accessing hard-to-locate archival film. The consumption of pirated film media lives on, creating generation upon generation of new pirates exploring the digital film archives across cyberspace. This year, a Pakistani film called Joyland won Un Certain Regard at the 75th Cannes film festival and the Prix Queer Palm, too. It’s the first Pakistani film to premiere at Cannes, and it’s been described in the most recent edition of No Content Available by FAN programmer James Calver as a “poignant Queer love story” and “an amazing and contemplative experience”. Another Pakistani film, a harrowing documentary called Javed Iqbal: The Untold Story of a Serial Killer (2022) was banned in Pakistan, but it was selected for the prestigious Berlin Film Festival and exhibited across the United Kingdom.

There’s been an enduring hunger for Pakistani and Indian film in Britain for decades, from pirated VHS tapes in the 1970s to pirating Slackistan in the 2010s. The current pique of interest in new Pakistani films with Joyland and Javed Iqbal proves that the appetite is alive and kicking, with a huge benefit to exhibitors, filmmakers, film festivals, audiences, and funders from the Pakistani and non-Pakistani community alike. Let’s hope the interest is mirrored in heightened exhibition, circulation, DVD production, and availability of these films and other Pakistani films on streaming sites, so we learn from the mistakes of the past to serve audiences of all backgrounds to make film more widely available.

Special thanks to Moira McVean and Caitlin Lydon for their invaluable support on this piece.